22. PID controller in practice

While we have seen how the PID controller works so far, we had restricted our view to an ideal scenario: linear systems.

Linear systems have virtually no limitations, and respond “linearly” (of course!) to any command.

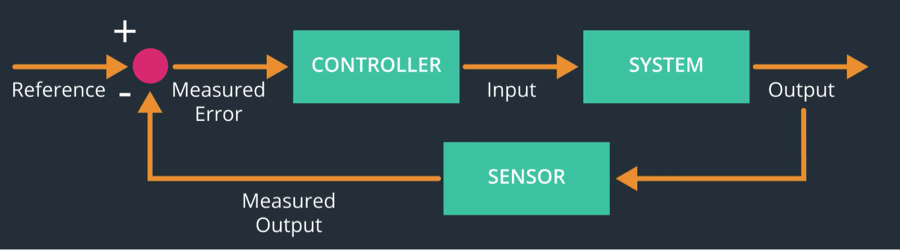

To understand what we mean by that, let’s recall what the output of the controller is. In the previous lecture’s example, we were dealing with thrust, which was applied to the behavior of our drone.

In a real-world scenario, instead, this thrust gets transmitted to the drone through actuators. These actuators are not linear systems; instead, they have physical limitations, and can’t entirely follow the commands given to them.

Saturation is one of these limitations. It limits the ability of the actuator to follow a given command. This limit affects the integral part of the PID controller.

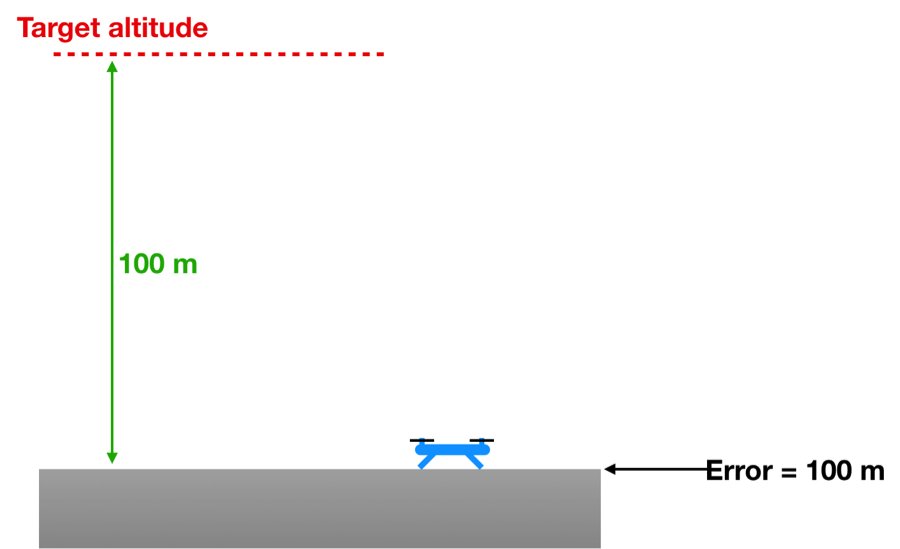

Let’s use the same example introduced in the previous lecture. Our initial state will be the same: the drone is staying on the ground waiting to lift off and reach the target altitude. This time, though, the motor spinning the propellers will have a limitation to the thrust it can provide. Let’s say that the max thrust is 200N.

If our drone is strapped to the ground, then the integral component of the PID controller will evaluate the past error (which is 100 meters), and will signal an increase of thrust. As long as the drone stays on the ground (and we are forcing it to), this accumulated error keeps growing, and the integral part will signal the motor to keep increasing the thrust.

At a certain point, we will reach an interesting situation, where the motor cannot provide the thrust requested by the controller, but the controller keeps sending a signal to increase thrust.

As long as the drone stays on the ground, the accumulated error increases and the requested thrust does as well.

Let’s say, for example, that the requested thrust has reached the value of 1,000N, but the motor can only deliver 200N.

As soon as we release the drone, it will quickly rise as the motor is requesting the maximum thrust. It’s easy to see that the drone will rapidly overshoot the target.

At this point, the error will become negative, and the commanded output will decrease. Interestingly, though, the commanded output will start decreasing from where it was before leaving the ground, which was around 1,000N.

The motor, on the other hand, will continue to produce 200N until the commanded output decreases below that value. Until that point, the drone has been rising with a 200N thrust!

The area between the commanded thrust and the engine limitation thrust is called “integral windup”.

We want to minimize this windup area, which means that we want to reduce the time it takes to reverse command when the error changes sign, to stop the integrator from increasing its output value.

A way to do that is to use “clamping,” which essentially turns the integrator off when we don’t want it to integrate any longer.

We won’t go in details on this topic, but we can provide some additional resources for you to read:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Integral_windup

http://www.20sim.com/webhelp/library_signal_control_pid_control_antiwindup.php